Do you dance? I have to confess I’m not a dancer myself, but that doesn’t stop me enjoying Strictly Come Dancing when it reappears on the television each autumn. Of course, I still encounter lots of dance music through my playing and I’m sure you do too, regardless of whether you have two left feet.

Knowing a little about the dance music we play is important as it helps us understand the character and style of each one. Initially I intended to cover both Renaissance and Baroque dances in this edition of the Score Lines blog, but it quickly became clear it was in danger of becoming overwhelmingly long! Instead I’m going to concentrate today on Renaissance dances and return to the Baroque period in a subsequent post. As you’ll see then, some of the dances simply evolved, but the Baroque also features some distinct dance forms of its own.

Where to begin?

When it comes to Renaissance dances an excellent starting point is Orchesographie. This is a treatise written by the French cleric Jehan Tabourot under the pseudonym Thoinot Arbeau - an anagram of his real name. Published in 1589, it describes the dances through a conversation between Arbeau and his student, named Capriol.

If that name seems familiar, you’ve no doubt encountered it through Peter Warlock’s Capriol Suite. This is a collection of six dances, composed for piano duet in 1926, where Warlock takes melodies from Orchesographie and creates his own music from them. It’s since been arranged for many different ensembles, include strings, symphony orchestra and for recorders too.

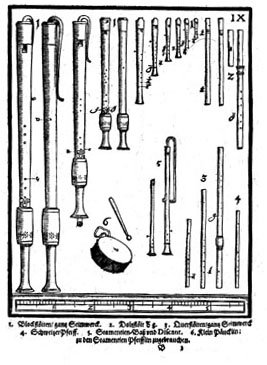

Orchesographie includes no fewer than 47 dance choreographies, including the dances I’ll talk about today. He includes history of the dances, advice about the behaviour of those dancing them, along with woodcut images and tablature illustrating the steps. This invaluable treatise is still available today, both as a facsimile of the original (you can download it free from IMSLP here) and in an English translation, published by Dover Books.

Let’s now take a look at the Renaissance dances you may meet while playing the recorder. We’ll explore the background to each one (including alternatives names used for many of them), the style of dance and some examples of each.

Pavan

Pavane, pavana, padovana, paduana

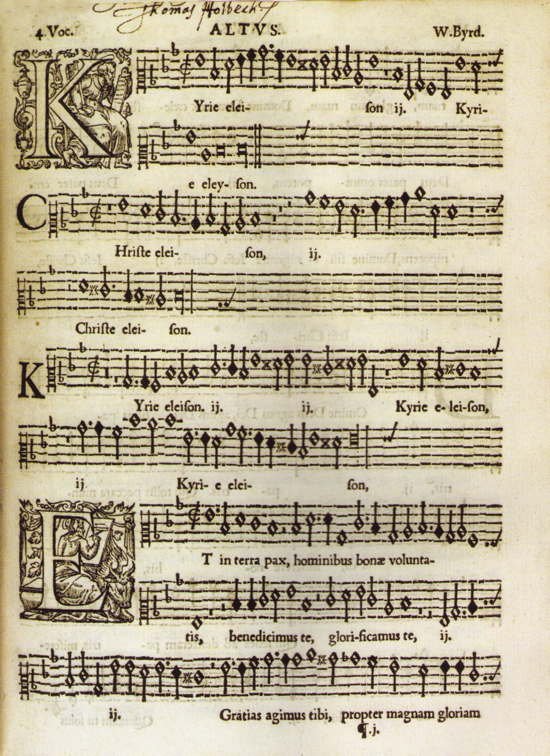

One of the Pavans from Orchesographie - click to see enlarged.

The Pavan (along with the galliard) is perhaps the most familiar dance from this period. The earliest known example was published in Joan Ambrosio Dalza’s Intabolatura de lauto libro quarto in Venice in 1508. It gradually grew in popularity, peaking in the mid 1500s and dying out by the end of the 16th century. However, its popularity as a form of music continued well beyond that and there are many examples from more recent composers such as Fauré and Ravel.

The Pavan is a stately dance in two time, for many couples in a procession, slowly circling the ballroom. The choreography is quite simple, with backward and forward steps and moments where the couples rise on the balls of their feet and sway from side to side. The steps can also be ornamented if the dancers desire. Arbeau describes it as an opportunity for the them to display their elegant attire.

Dances often come in pairs (this is equally true in the Baroque period) and the Pavan is often followed by a Galliard (of which we will learn more shortly) as you can see in the following example.

Holborne Pavan & Galliard

Perhaps the most famous Pavan is John Dowland’s Lachrimae, his signature tune, to which he later added lyrics to create the lute song Flow My Tears.

Dowland Lachrimae Antiquae - Jordi Savall & Hespèrion XXI

Galliard

Gaillarde, gagliarda

Often paired with a pavan, the Galliard is a livelier dance, in three time, popular throughout 16th century Europe. It’s a carefully choreographed dances, where the dancer hops on one foot while making a flick of the other foot, as if to kick someone, interspersed with bigger leaps.

While the dance is quick, the music must be slow enough to accommodate all these detailed steps. Arbeau notes that the music will need to be slower when playing for big men as they will take longer to execute these steps than a man of smaller stature. He also urges dancers to control their movements so the ladies don’t show their knees and to take care not to kick one’s partner!

The Galliard was reportedly one of Queen Elizabeth I’s preferred dances, despite its vigorous nature. In 1589, when the Queen was already in her mid-fifties, John Stanhope of the Privy Chamber reported,

“the Queen is so well as I assure you, six or seven galliards in a morning, besides music and singing, is her ordinary exercise.”

Byrd Galliard a 6 - Fretwork

Almain

Almand, allemande, allemanda, alman

The Almain is a livelier dance than the Pavan but not wildly energetic. The music has two beats per bar and Arbeau describes the dancers as processing hand in hand in pairs, walking for three steps and then balancing on one foot. Later versions of the dance used three springing steps and a hop. Over time the Renaissance Almain developed into the Baroque Allemande which we’ll look at in part two of this series.

Ferrabosco Almain in D - English Cornett & Sackbut Ensemble

Coranto

Courante, corrente, corant

The Coranto is a brisk dance whose title derives from the Italian word to run. Arbeau describes it as having fast running and jumping steps, although curiously he also describes it as being played in two time, when most music of this title has three beats per bar! The dance continued its evolution, becoming the Courante during the Baroque period.

Byrd Coranto - Buffalo Guitar Quartet

Towards the end of his 1599 collection of dances Antony Holborne includes a number of Corantos. Perhaps the most famous is The Fairie Round, which perpetually shifts between 3/2 and 6/4 rhythms, although these changes often happen independently in different parts. This offers many challenges for the musicians playing it and I can’t help wondering whether he intended the music to be used with dancers. The myriad of cross rhythms would certainly make their life exciting too!

Holborne The Fairie Round - David Munrow & Early Music Consort of London

La Volta

Volta, volte

An example of Arbeau’s choreography notation for La Volta - click to see enlarged

This was reportedly another of Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite dances, although it was considered to be somewhat vulgar by many. Like the Galliard, it has a brisk three beats in each bar and is danced with hopping and jumping steps. But the risqué element comes when the man lifts his partner, holding her corset, while turning - tame compared to today’s ballroom dances but no doubt quite shocking for the 16th century!

Byrd La Volta - The Academy of Ancient Music

Branle

Bransle, brawl

The Branle is another brisk dance, this time in two. The name comes from the French word branler which means ‘to sway or shake’ and this is reflected in the sideways, swaying steps. As with so many historic dances, the Branle was danced differently depending on where you were in Europe. It has many varieties, including a number named after different regions of France. Arbeau gives choreography for no fewer than eight different varieties of Branle!

Branle de Bourgogne - Bavarian Brass

As an additional example this one rather tickled me - the Washerwoman’s Branle, performed in a launderette!

Basse dance

The Basse dance, or low dance, was a popular court dance in the 15th and 16th centuries. Its name reflects its choreography, where the dancers’ feet glide gracefully, barely leaving the floor. Like the Galliard, it’s in triple time, but often played at a more measured pace. Another similarity to the Galliard comes with its use of hemiolas, where two bars of three are grouped to feel like three bars of two.

If you’re familiar with Warlock’s Capriol Suite you’ll recognise this example which features the melody used in Orchesographie.

Arbeau Basse Dance - Praetorius Ensemble & Christopher Ball

Basse Danza Lauro

That completes our quickstep through the dances of the Renaissance period. It’s been fascinating to explore the different dance types and to see their choreography and if that has whetted your appetite to learn more there are endless videos available on YouTube. I’ll return to this topic again in a few weeks time with a look at dances from the Baroque period. Here we’ll encounter some familiar dance names, albeit with choreography which has evolved along with the music.