Whatever job you do for a living, the chances are you had some training at the start. Surgeons start about anatomy long before they operate on a human, and lawyers are taught the intricacies of the law before they’re sent into court to defend someone’s freedom. Likewise, a professional musician spends many years at music college or university gaining a rounded understanding of music theory and the history of the repertoire we later play and teach.

I meet many able amateur musicians who are highly qualified in their own fields of work, but have come to music making by a more circuitous route. Maybe they learnt the basics at school and returned to music making several decades later. Or perhaps they decided to learn an instrument when they retired. One common factor I frequently see is a patchy knowledge of music theory, picked up piecemeal as they’ve learnt to play new repertoire.

I also see this from a personal perspective with my photography. I’ve learnt a handful of skills to help me tweak my photographs in Photoshop, but my knowledge is far from complete. Rather than learning this complex piece of software from the ground up, I’ve picked up pieces of information as and when I need them. The result - I can do certain things, but gaps in my knowledge leave me floundering when the task in hand moves beyond my limited understanding. Even worse - I often don’t know exactly where the gaps in my understanding are, which makes them even harder to fill!

With this in mind I recently asked my Score Lines subscribers about areas of music theory where they felt they had gaps. This is the start of a new series of blog posts to help you begin to plug the holes in your knowledge and gain greater enjoyment from the music you play. Among the responses to my plea were several asking about time signatures and how they interact - especially in Renaissance music.

This seems as good a place as any to begin. So let’s dig in!

Understanding time signatures

Let’s begin with the basics - what is a time signature?

Those numbers at the beginning of our music tell us how many beats there will be in each bar. They also explain what type of beats we’ll be counting in and whether they subdivide into twos or threes. Here’s how to decode them…

Let’s begin with perhaps the most familiar time signature - 4/4.

The top number

The top number of any time signature tells you how many beats there are in each bar - in this case four. It really is as simple as that. If the top number is 2 there are two beats in the bar, if it’s 10 there are ten of them. How you feel those beats can be a touch more complex, but we’ll come to that later.

The bottom number

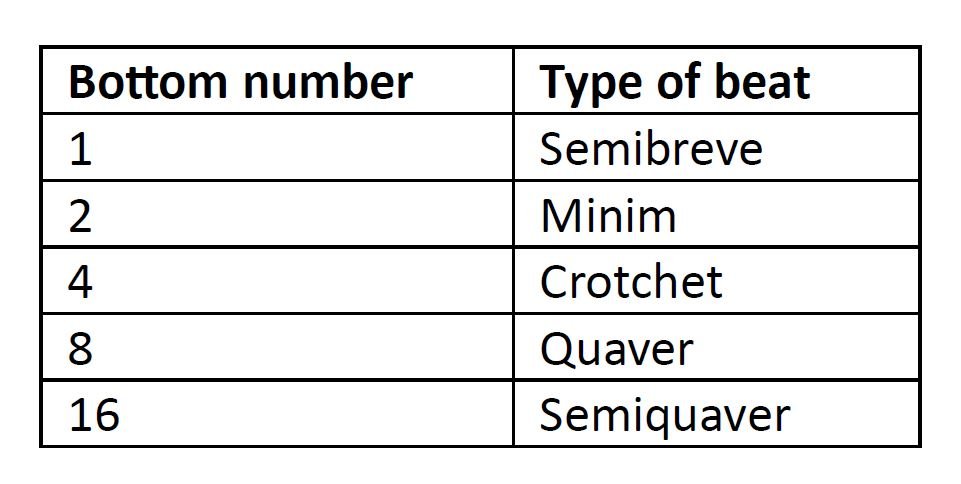

Now for the bottom note of your time signature. This indicates the type of beat you’re dealing with, as you can see in this table:

Now you know these two pieces of information you can at least identify the number and type of beats.

Simple and compound time

Aside from the actual beats we have in each bar, another important element to understand is whether the music is in simple or compound time. These terms refer to whether the main beats in the bar (the pulse we feel when we tap our feet in time with the music) divides into two or into three. Let’s begin by listening to two pieces which illustrate the way these feel.

Simple time

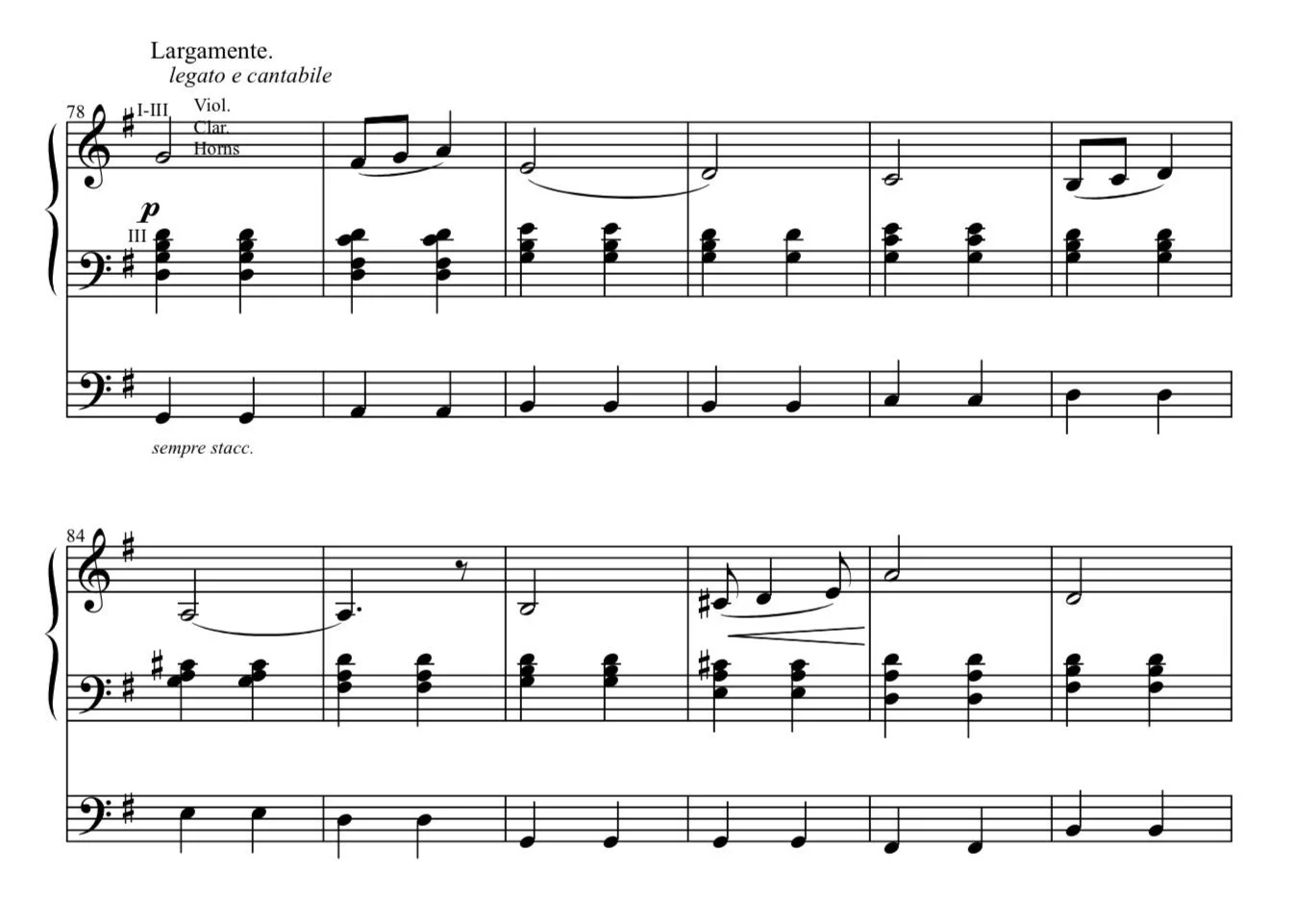

When the pulse subdivides into pairs of notes, the music is said to be in simple time. For instance, in a piece built upon crotchet beats those notes each divide into two quavers. Listen to this recording of Elgar’s famous Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 and count along to the beat - one - two, one - two. When you subdivide the beats they break down into pairs of quavers - as you can see in the extract below. This means the music is in simple time.

Simple time comes in many different forms, but if the main beat is a quaver, crotchet or minim it naturally divides into two halves. Here are a few more examples of pieces in simple time:

Gabriel Faure - Pavane, Op.50: Four crotchet beats per bar, each of which divides into two quavers.

Handel - Hornpipe from Water Music Suite No. 1: The lower number of the time signature indicates a minim beat, and these subdivide into two crotchets.

Vivaldi - Autumn from the Four Seasons, 3rd movement: Here we’re dealing with a quaver beat and each of these divides into two semiquavers.

Finally we have Marg Hall’s Klezmer Fantasia. It may have an irregular number of beats in each bar, but each one of these splits into two quavers. We’ll come back to irregular time signatures like this again a little later…

Common time and other curiosities

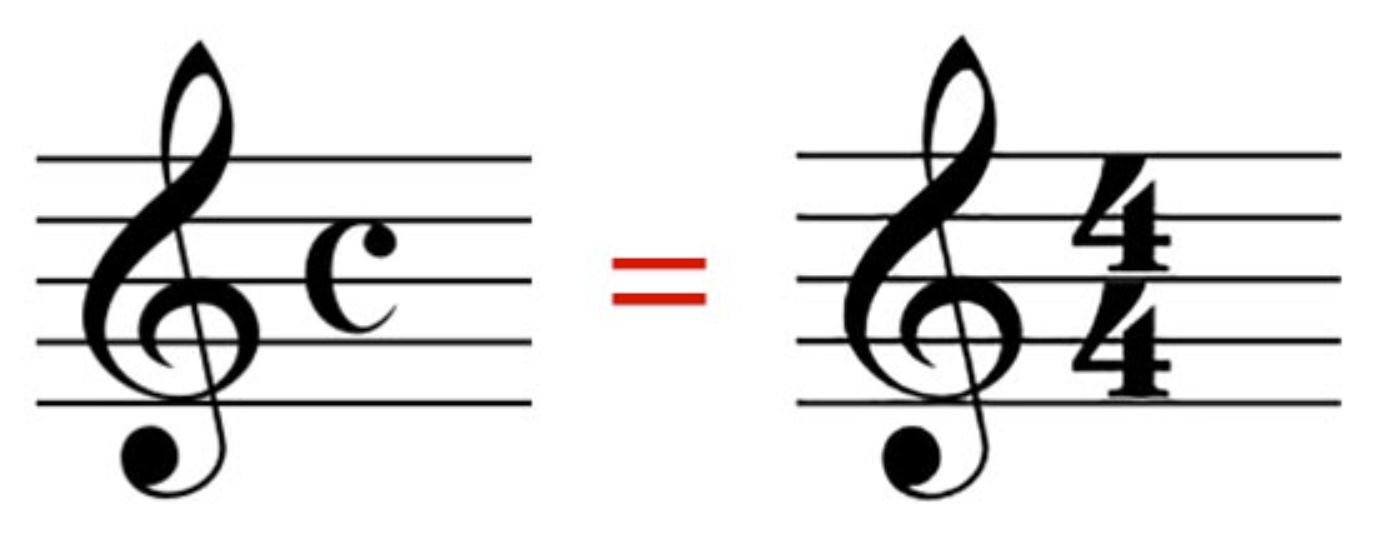

While most time signatures are notated as numbers, sometimes the letter C is used. This is a historical throwback, connected to the mensuration symbols used in the 16th century and earlier, before music had bar lines. In short, C (often known as Common time) means the same as 4/4.

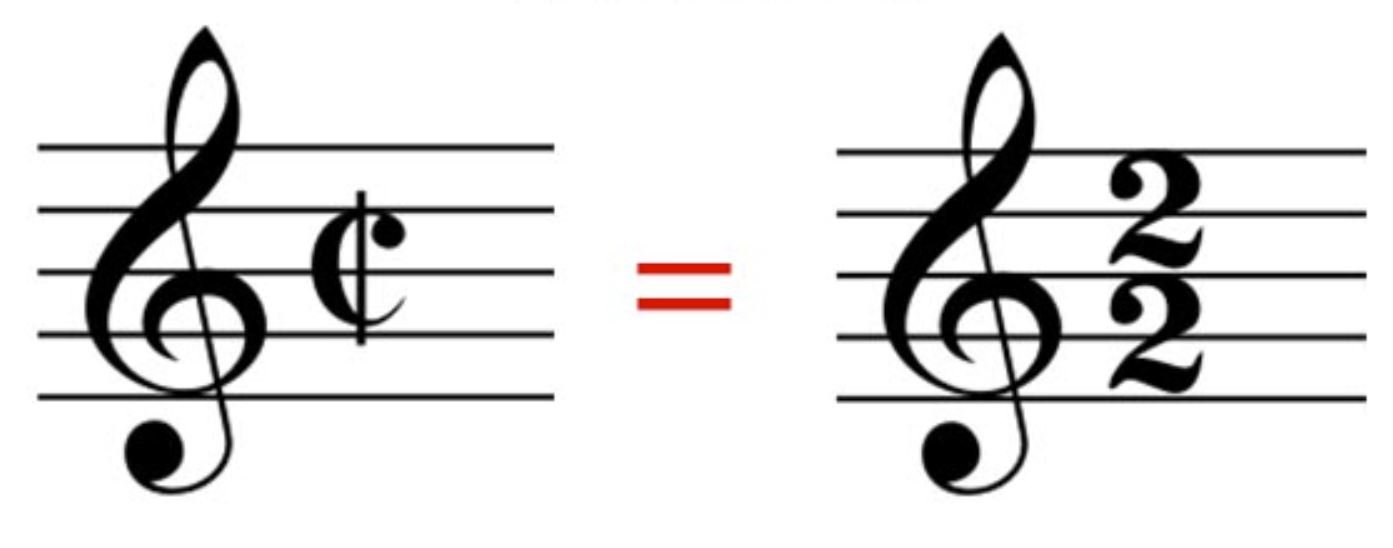

When the letter C is divided with a vertical line (often called Cut Common time) it usually means 2/2 time, although in early music it is occasionally also used to indicate 4/2 time. If you’re interested to learn more about this, do check out my post called Cracking the Code from 2021, where I talk in more depth about the vagaries of Renaissance notation, including the evolution from mensuration symbols to time signatures.

Occasionally you’ll also come across simplified time signatures in early Baroque music, where the composer just gives a single number. In such situations this number equates to the top number of a modern time signature. It’s up to you to look through the music and figure out which type of beats are involved. In the example shown here we’re dealing with crotchet beats so a modernised time signature would be 3/4.

Compound time

Not all music subdivides neatly into pairs of notes - sometimes the main beats divide into thirds - this is called compound time.

Let’s take a look at an example – Barwick Green, the theme music for the radio soap opera The Archers, by Arthur Wood. As you listen, note how the music has a ‘rumpty tumpty’ sort of feel, common in a lot of folk music.

If we consider the time signature of 6/8 and use the advice I gave earlier it’s easy to assume we have six quaver beats in the bar and each of these subdivides into two semiquavers.

Yes, this is true, but listen to the music again and tap along with it. Are you tapping the quaver beats? I bet you’re not! No, in this sort of music we feel a larger size of beat - in the case of 6/8 that’s two dotted crotchets in each bar. Each dotted crotchet breaks down into three quavers and that’s what makes 6/8 a compound time signature.

6/8 is probably the most familiar compound time signature, but there are others too. If you want a basic principle to work by, you should look out for time signatures where the top number is divisible by three, such as 9/8, 6/4 or even 15/8. This doesn’t apply if the top number is 3 though, as those are still simple time signatures.

Let’s do the same as before and check out some real world examples:

Bach - Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV537: The time signature for this piece is 6/4, so each bar contains six crotchet beats. These are grouped into two dotted minim beats. In the first bar there are two dotted minims in the lowest voice and elsewhere the quavers are beamed together in groups of six, whose combined length is a dotted minim.

Corelli - Pastorale from Concerto Grosso, Op.6 No.9: Twelve quaver beats in each bar, but these are grouped into four dotted crotchet beats.

Putting your knowledge into practice

Knowing how to identify and translate a time signature is one thing, but that’s just the first step - now we have to put this into practice so we can actually count the music we’re playing.

Is there a difference between the pulse and beat?

This is a question I’m often asked, and the simple answer is that the pulse and beat are fundamentally the same thing. The term pulse is most commonly used to refer to the gentle throb a nurse feels for in our wrist to check how fast our heart is beating. The pulse in music has the same function, recurring at regular intervals through a piece. If you tap your foot in time with music it’s the pulse you’re tapping along with.

The term beat can often be used as a synonym for pulse in music, but it’s used in other ways too. For instance, a conductor beats the time signature with their hands or a baton, but again they’re visibly indicating the pulse or beat, just as you might by tapping your foot. You may well have heard conductors using both terms and that’s where confusion often occurs - I’m sure I’ve been guilty of doing exactly this at times!

How do I know which beat to feel/count?

Knowing which type of beat to feel when playing a piece of music is dependent on several things:

The style and character of the music

The tempo (speed) the composer has specified

Your own level of technical proficiency.

Let’s look at three different scenarios…

Simple time signatures

When faced with a piece of music in 4/4 time, the logical approach is to count four crotchet beats in each bar - after all, that’s exactly what the time signature means. Take this extract from Handel’s Water Music, for instance. The C at the start means 4/4 time and, when played at the traditional Andante sort of speed, it makes perfect sense to feel four crotchet beats in each bar - as you can see from the beat numbers I’ve added in red.

Now let’s look at a snippet from Francesco Mancini’s Recorder Sonata No.10. Here you can see we have the same time signature but the tempo indication (Largo) is slower than in the Handel. It’s entirely possible to feel a crotchet beat in this music, but the speed will probably be around 50. For many people this will feel very slow and there’s always a temptation to rush. One alternative is to subdivide the beat in your head, counting one-and-two-and etc. as I’ve shown in the music below:

A second option is to feel a quaver beat, resulting in eight quaver beats per bar, as shown below. The metronome mark of these quaver beats would be 100 to achieve the same performance speed. This may make it easier to read the rhythms and analyse the length of the notes, but there’s a risk the music can become a bit too ‘beaty’ because you’re feeling eight pulses in each bar rather than four. It’s a matter of personal preference. If you begin counting eight quaver beats you may find you can gradually slip back into feeling the slower crotchet beat as you get to know the music better.

Minim beats

This is a thorny issue for many recorder players and a topic of conversation in many rehearsals. Look through a pile of music from the eighteenth century or later and you’ll see that most music in common time is written in crotchet beats. We spend a lot of our musical lives counting in crotchet beats and these are the notes we’re first introduced to when we begin to read music.

But this hasn’t always been the case. If you delve back into music from the 16th century and earlier you’ll find much of it is written in minim beats, or sometimes even semibreve beats. To our modern eyes this notation looks slower because there’s an absence of the smaller note values. During the first decades of the early music revival in the 20th century, music editors often sought to make this music easier to read for modern musicians by creating editions where they halved the note values. Since then the needle has swung back towards a preference for authenticity in notation, allowing us to see the composer’s original intentions. As a result most modern editions of early music now retain the original time signature.

As with the Mancini example above, you could subdivide the minim beats into crotchets. In this extract from Byrd’s Fantasia I à 4 I’ve marked up the first two bars with numbers showing the minim beats. From bar five I’ve changed that to crotchet beats and you can see how much busier it looks. If you’re trying to think about two beats for each minim that’s an awful lot of mental activity in every bar. Once again the music will be in danger of feeling too ‘beaty’ and there’s a good chance you’ll slow down too.

I know a lot of musicians find it difficult counting in minim beats, but I would argue this is largely down to a lack of familiarity. We find comfort in things we know well and unfamiliar skills will always seem harder. But if we work at it, these skills become more familiar and less scary!

One solution I sometimes hear suggested is to ‘translate’ the longer note values back into something more familiar. For instance, a minim in 4/2 would be a a crotchet beat in 4/4. It’s similar to the way we mentally convert between currencies when shopping in a foreign country. But in music we need to do it in a split second while also reading the pitch of the notes, plus accidentals, articulations and dynamics!

A better solution is to take a moment before you sight read a piece to think about the relative speeds of the different note values. Spend a few seconds looking at the minims and tapping them at your chosen tempo. Then half the speed of your tapping while looking at the semibreves. Finally, double your minim speed to tap the crotchets. Over time you’ll be able to work these out more quickly, and after a while you’ll wonder why you ever found counting in minim beats so hard!

Compound time

Having dealt with simple time, the principles are very similar for compound time. The type of note value you choose to feel while playing will depend on the character and mood of the music. Let’s look at the examples I used earlier.

With Barwick Green (The Archers theme tune) you would naturally feel two dotted crotchet beats in each bar because the tempo is Allegro. To try and feel six quavers in a bar would quickly have you tied in knots!

That said, if the music is very fast your choice of speed may be dictated by your own technical limitations. For instance, if you decided to play Barwick Green and found the quavers were too fast to play at full speed, it might be better to begin at a slower tempo, counting six quaver beats in each bar. As your fluency improves you can gradually increase the speed and eventually you’ll reach a point where you can adjust back to a dotted crotchet pulse instead of quavers.

In contrast, the Bach Passacaglia is usually played at quite a slow tempo, perhaps crotchet = 72, so you would naturally count six crotchet beats in each bar, as I’ve marked below. At this tempo the dotted minim beat would be 24, which is far slower than any mere mortal can sensibly maintain!

With both simple and compound time signatures, your choice of beat will be influenced by the tempo of the music and the character you’re trying to bring to the music. The trick is to figure out what the possibilities are and make your decision according to which feels right and/or which is easier. As you get to know the music better you may decide you prefer to feel fewer beats per bar - you’re absolutely allowed to change your mind!

Irregular time signatures

I promised to come back to unusual time signatures, such as 5/4 or 7/8. These irregular time signatures can often feel uncomfortable, purely because of their irregularity.

As humans we have two of most things - eyes, ears, legs, hands etc. and because of this we like music which has a predictable left-right-left-right sort of feel to it. Music in triple (three) time doesn’t fit this description, but it does still have a regular lilting feel (think of a waltz) which comes quite naturally.

However, a time signature like 5/4 has an instant imbalance to it. A bar with five beats cannot divide neatly into two equal halves - instead you have either 3+2 or 2+3 beats. Most composers tend to set up a regular pattern in such time signatures, only deviating from it periodically. Take this short extract from Mars from Holst’s Planets, for instance. You can clearly see the bars are broken into three beats and two beats - I’ve marked the dotted minims (three beats) with triangles and the minims with square brackets. This is very consistent in every bar.

When counting a piece like this in 5/4 you have two choices. The first is to count a consistent five crotchet beats in every bar, while the alternative is feel two unequal beats per bar - in this case a dotted minim followed by a minim. This choice will almost certainly be influenced by the speed of the music. If your metronome marks is crotchet = 100 you’re probably best off counting in crotchet beats. On the other hand, if you crotchet beat is 160 it may be easier to feel a lopsided two in a bar. What you absolutely mustn’t do is add an extra beat to turn the music into a nice, balanced 6 beats per bar!

When you have to make a decision like this it’s often best it look at the full score rather than just your own part. Seeing all the voices together can make it clearer how the music break subdivides - as you can see in the extract from Marg Hall’s Klezmer Fantasia which I’ve marked up below:

If you’re playing a piece like this in a conducted group your conductor will probably explain how the music breaks down, so do pay close attention to what they’re saying!

Time changes in Renaissance music

I’ll complete this exploration of everything related to time signatures with a look at the thorny issue of time changes in Renaissance repertoire - a topic I’m often asked about.

It’s not unusual for music from the 16th century to switch from duple (2) time to triple (3) time in the middle of a piece - and sometimes back again. Of course this happens in later music too, but Renaissance repertoire is a special case because there is usually a mathematical relationship between the two time signatures. The exact nature of this relationship is not always clear and then you have the practical matter of transitioning from one to the other to consider.

During the 16th century there were two relationships between the time signatures. At the time they had different names…

Sesquialtera

This is where a whole bar of the duple time signature is the same duration (i.e. occupies the same length of time) as the new triple time. In Victoria’s O Magnum Mysterium shown below, I’ve marked the time change in red. Treating this as a Sesquialtera, the 3/2 bars would be the same length as the preceding duple time bars (each of which is a breve long), making the new minim beat very slow.

Tripla

This is the term used when the length of the new triple time signature is the same length as half of the preceding duple time. Looking back at the Victoria example above, I think this approach works much better. The new triple time bars are then the same length as the semibreve beat (half a bar) in the duple time. As a result, the minims in the triple time section are faster than in the preceding bars.

How do I tell a Sesquialtera from a Tripla?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if there was a clear way of knowing which piece requires which approach? Absolutely it would, but sadly notation during the Renaissance was far from consistent!

Sometimes editors of modern editions will give an indication as to how they think the music should be played, showing a sort of musical equation above the score. For instance, at the change in the Victoria shown above you might see something like this:

With such a lack of clarity in the original sources the most practical approach is to try both the Sesquialtera and Tripla and see which works best. Usually one will work better than the other. In my experience the Tripla tends to occur more frequently but this is far from a fixed rule.

Practical tips for time changes

One of the questions I’m asked most often about Renaissance music is how to negotiate these sorts of time signature changes when playing. It’s all very well if you have a conductor to lead you through this minefield but I know many smaller, self-led groups struggle to figure this out. To explain the process we’ll use the Victoria O Magnum Mysterium again. Below you’ll see a short extract from the full score, which I’ve annotated, but if you’d like to refer to the whole score you can download it here.

In order to decide whether you’re going to treat the time change as a Sesquialtera (whole bar = whole bar) or a Tripla (half a bar = a whole bar of the triple time) you need to figure out the relationships between them. To explain the options you’ll see I’ve added some metronome marks. If you want to hear these speeds for yourself you can use your own metronome, or just click on the words where they’re highlighted in the text below and you’ll hear the tempi courtesy of YouTube.

Let’s begin with the Sesquialtera option…

I would normally play this piece at around minim = 120 and that means a semibreve (half a bar) = 60 and a whole bar is breve = 30. It’s very difficult to really feel 30 beats per minute as it’s so slow - that’s where a metronome can be very useful.

Looking ahead to the time change, making it a Sesquialtera means the new triple time bars (which are a dotted semibreve long) are the same length as the breve in 4/2. Now you know this, you just need to multiply the breve’s metronome mark (30) by three to find out your minim beat, which is 90. As I mentioned earlier, that means the new minim beat is still pretty slow and I find this relationship quite hard to feel instinctively.

Sesquialtera - a whole bar of the new 3/2 time signature is the same length as a whole bar of the preceding 4/2.

If the Sesquialtera doesn’t feel natural, let’s see if the Tripla works better…

Here the opening speed remains the same, but the new 3/2 bars are the same length as half a bar of the 4/2. Therefore the semibreve = 60 of the 4/2 becomes a dotted semibreve = 60 in the new 3/2. To find out the new minim beat multiply by three, which makes them minim = 180. Yes, this is a fast beat, but it makes for a livelier effect and I think it creates a more natural relationship between the two time signatures.

The process I’ve described above is what I do when I’m preparing to work on a piece of Renaissance music like this with an ensemble. I work out the relative speeds for both Sesquialtera and Tripla and decide which seems more natural. If I’m honest, I probably opt for the Tripla more often, but it’s good to explore both.

Putting the time change into practice

Having decided which option you’re going to use, the next task is to put your decision into practice. With time and experience you may find you’ll begin to make these transitions instinctively, but I have some tips to help you get to that point. Again, I’m using the Victoria as a practical example - you can download the complete score here if you haven’t already done so.

Break the piece down into sections. Having decided on your opening speed, begin by practising all sections which share the same time signature. In the case of the Victoria this means rehearsing from the beginning up to bar 52 and from bar 67 to the end. After a few repetitions the music will begin to feel familiar and you’ll develop some ‘muscle memory’ for this speed.

Practise the 3/2 section separately. Now use your metronome to remind yourself of the new speed at the 3/2 and play this section. Try playing it with a minim beat or the slower one-in-a-bar dotted semibreve beat and see which feels better for you. Repeat the section several times so the speed becomes really settled in your mind. Do check back with your metronome to ensure you’re maintaining the new tempo.

Now practise the transitions. This is where you combine the two time signatures. By now you should be comfortable playing the different sections, so try moving from one to the other and the muscle memory you’ve built up will carry you across the joins.

You can use this process for any piece of music with abrupt tempo changes like this, whether it’s from the Renaissance or any other period of music.

~ ~ ~

Has this completed some of the gaps in your knowledge? Or maybe you still have questions? Answering one question often reveals other areas you’d like to know more about, so please do leave a comment below with your thoughts. My aim is always to broaden your musical knowledge and the most efficient way I can do that is by responding to your needs - I’d love to hear your ideas and requests!