For many people the first image to come to mind when the recorder is mentioned will be the descant they encountered during their school years - quite possibly a plastic one, played very badly. But those of us in the know understand our favourite instrument has many more facets. Even so, many recorder players are really only familiar with mass produced Baroque style instruments, whether they’re made from plastic or wood.

Throughout history, the music composed for the recorder has changed, and the instrument has evolved in parallel to suit new fashions and styles. This is the first of a series of blog posts about the recorder’s different characteristics, exploring the way the instrument’s design has changed over the last six centuries. Today I’m going to talk about Renaissance and Baroque recorders. Since the recorder’s revival in the early twentieth century there have been many more developments, but I’ll talk about those in a subsequent post.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with using Baroque style recorders to explore our varied repertoire, but maybe this will open your eyes to the way a historically appropriate design of recorder can influence the way music from different periods is performed.

The Medieval period

The oldest surviving recorders date back to the fourteenth century. The best known is perhaps the Dordecht recorder, found in the Netherlands in 1940. These ancient instruments are a simple design, made from a single piece of wood, but they share the recognisable features of our modern recorders - a windway created by the insertion of a fipple (the block) into the mouthpiece and a thumb hole to allow for a greater range of notes than a simple whistle. Sadly many of the surviving recorders are in poor condition as their wooden construction made them prone to damage or decay after they were discarded.

Renaissance recorders

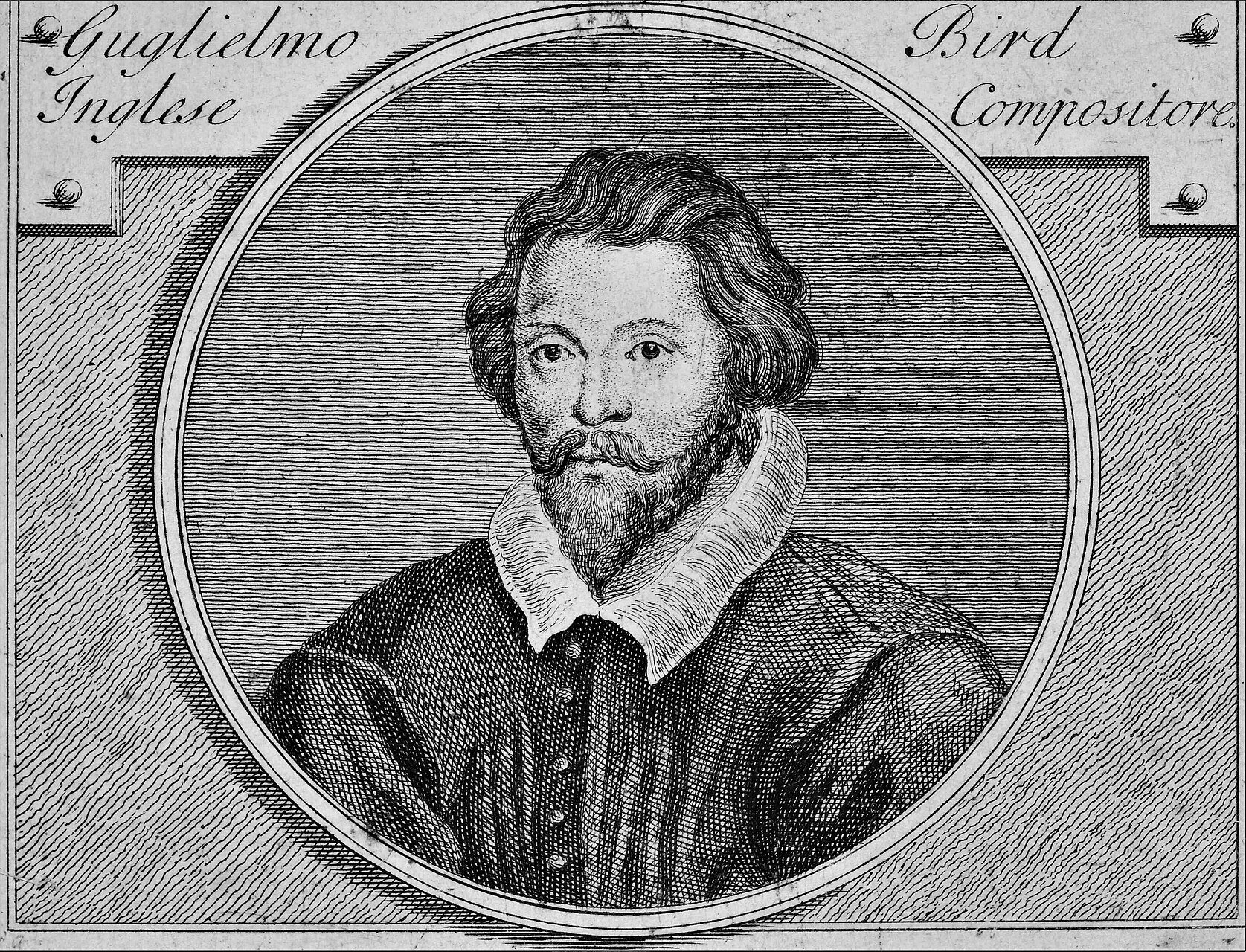

By the time we reach the Renaissance period, we not only have a much larger array of surviving original instruments to study, but plenty of imagery too. This illustration, taken from Michael Praetorius’ treatise Syntagma Musicum (1614-20), clearly shows a sizeable family of recorders, from tiny to large.

The Renaissance look

Renaissance recorders look very different to the Baroque ones we often play today. The smaller instruments, from the tenor upwards, were usually made from a single piece of wood, while the larger recorders were creates in two pieces. Their outline tends to be very simple, with few decorative features - a straight body with a flared bell.

Another detail you may notice from the image above is the appearance of two holes for finger seven (clearest on the 6th recorder from the left). This allows the instrument to be played with the left or the right at the top and the unused hole would have been filled with wax. Larger recorders needed keys to make the lowest notes playable and these were made with a characteristic butterfly shape for the same reason. It’s normal to play with the left hand uppermost today, but if you study paintings from this era you’ll see they feature both left and right handed recorder players fairly equally.

A consort of recorders by Adrian Brown, based on an image from Sebastian Virdung's treatise Musica getutscht. The recording below was performed on a consort like this.

The elegant butterfly keys were only necessary for the larger sizes of recorder - certainly on basses and on some tenors too. The lower part of the key was often covered with a fontanelle made of perforated metal or wood. This protected the vulnerable mechanism, but added a decorative element too. The holes in the fontenelle also allow air to escape - without these it would have a negative effect on the tuning.

You might think that having instruments made from a single piece of wood would create difficulties with tuning – after all, you can’t adjust the pitch of a single piece recorder by pulling out the headjoint. Recorders of this period were almost always made in consorts at one pitch, so this was less of a problem than we would consider it today.

Most Renaissance bass (or basset as Praetorius calls them) recorders were direct blow models, although you need longer arms to play these compared to modern knick basses. Larger bass instruments existed too, the longest of which is listed in the inventory of Queen Mary of Hungary. It’s described as being a ‘baras’ in length - that’s about two and a half metres! For these largest recorders a crook or bocal is needed to carry the player’s breath to the windway, as you can see in the Praetorius image earlier. The video below features the Royal Wind Music performing on a consort of low recorders and you can see at close quarters the additions needed to make the biggest ones playable!

Not just recorders in C and F

Today’s recorders tend to use mostly C and F fingerings, but Renaissance recorders weren’t so consistent. Consorts of instruments were often pitched a 5th part - for instance a basset in F, a tenor in C, a treble in G and perhaps even a descant in D. These letters always refer to the lowest note of the recorder. To our modern brains playing recorders in G and D might require greater mental gymnastics than we’re used to, but I’m sure Renaissance musicians were entirely comfortable reading at any pitch, playing from a greater variety of clefs than we expect today too.

Renaissance tone begins inside the recorder

While Renaissance recorders look simpler on the outside, the shape of the internal bore is also very different. Inevitably this varies between the historical instruments which survive today, but they all have certain similarities. The bore tends to be mostly cylindrical, but with a noticeable flare at the bottom end. It’s this internal shape that influences the characteristics of the recorder’s tone and response.

Recorders from the Renaissance, often have a slightly smaller range than Baroque models - sometimes as little as an octave and six notes. Most music echoed the range of the human voice though, so this wasn’t a great restriction for composers. The lowest notes tend to be much richer and stronger, often demanding greater reserves of breath to fill out the tone. Because of this strength of tone more incisive articulation is also possible, making it easier to bring out the complexities of counterpoint and melodic shapes we so often see in Renaissance music. You can hear this clearly in Sirena’s performance of La Lusignola by Tarquinio Merula.

Fingerings and pitch

Most mass produced modern recorders are played with a pretty standard set of fingerings. The different bore shape of Renaissance recorders requires some variations on these fingerings. For instance, the ninth note from the bottom (middle D on a tenor recorder, or G on a treble) would have been played by covering none of the finger holes rather than using finger 2 as we would today. Handmade professional consorts of Renaissance recorders, such as those by Adrian Brown or Tom Prescott, retain these authentic fingerings. However, many of the more affordable consorts by makers such as Moeck and Mollenhauer, have been tweaked to allow the use of the more familiar modern fingerings.

Some time ago I shared a blog about the history of pitch, where we discovered that the standardisation of musical pitch is really quite a recent concept. During the Renaissance period music was generally performed at a higher pitch than we would expect today, and as a result some modern copies of old instruments are made at A=466. This is a pitch of convenience which has become internationally recognised, but it wouldn’t have been the case then. Instruments would have been crafted to match the pitch of instruments which can’t easily be adjusted, such as church organs, and pitch would probably have varied from village to village. The solution was to make recorders in matching consorts so you could make music together - undoubtedly why King Henry VIII’s inventory lists no fewer than 76 recorders!

Before you buy…

If you’re thinking about purchasing some Renaissance style instruments it’s important to consider how you’ll use them first.

Many professional ensembles commission a matching set of consort instruments from their preferred recorder maker. This creates a well matched sound and makes the tuning easier. Such instruments are often pitched at A=466 - around a semitone higher than modern concert pitch. If you only play the recorders together this is fine, but it’s probably more practical to stick with A440 if you want to have the flexibility to play with others.

The Renaissance instruments offered by the mainstream recorder brands are a good place to start if you want to dip your toes into this sound world at a more modest price point. I use Mollenhauer’s Kynseker instruments, but there are similarly priced Renaissance instruments available from Moeck and Peter Kobliczek, and it’s worth keeping a lookout for instruments for sale secondhand.

The Ganassi recorder - reality or myth?

In his 1535 treatise Opera intitulata Fontegara Sylvestro Ganassi reveals his discovery of a further octave of notes above those normally played on the recorder. He shares fingering charts for these additional high notes, noting adjustments which need to be made to one’s breath and articulation to achieve them.

The title page of Ganassi’s Opera intitulata Fontegara, featuring a consort of recorder players.

One thing Ganassi doesn’t include is a detailed description of the type of recorder required to play these notes. In the 1970s unsuccessful efforts were made to locate an original recorder capable of playing with his fingerings. In the absence of such an instrument, several contemporary makers, such as Fred Morgan, Alec Loretto and Bob Marvin, created their own designs to fill this gap. Externally they were modelled on pictures from La Fontegara, but much experimentation was needed to find the appropriate bore shape and level of flare at the bell to work with Ganassi’s fingerings. Ultimately the ‘Ganassi’ recorder is a modern creation, but still much loved by players today. I have a Von Huene Ganassi descant myself and love its rich tone, full low notes and the ease with which it plays the higher notes.

Baroque recorders - a change of purpose

The concept of the recorder as a consort instrument became less pervasive as time passed. There’s a small handful of pieces composed specifically for recorder consort (the Schmelzer Sonata à 7 is probably the most familiar) but in general the instrument took on a new musical role. As composers began to include the recorder in chamber music with other instruments and as the solo line in concertos a new sound and style was needed.

Whereas the Renaissance consort used the different sizes of recorder equally, during the Baroque the treble became the most popular size of instrument. The other recorders didn’t entirely fall out of use, but it was the treble that Bach, Telemann and Handel chose to use in their solo sonatas, cantatas, chamber music and concertos in combination with many other instruments. For instance, Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No.2 has four soloists, playing recorder, oboe, violin and trumpet.

Baroque elegance

At first glance the biggest change to the Baroque recorder is its external shape. Gone is the one piece design. Almost all recorders from this period (aside from some sopraninos and descants) are made from three pieces - the headjoint, body and footjoint. Creating breaks in the instrument adds points of weakness, so makers compensated by making the wood thicker here. These bulbous points added strength, but also created an opportunity for decoration - a stylistic feature we also see in Baroque architecture and fashion. Some makers took this to extremes, using complex wood turning and ivory rings.

The iconic image from Hotteterre’s 1707 treatise on playing the recorder, flute and oboe. The recorder’s decoration is as ornate as the player’s cuffs!

Another change to the Baroque recorder is the shape of the mouthpiece - often elegantly carved to look more like a beak. This has no effect on the tone, but was no doubt more in keeping with Baroque style and elegance. This feature also brought us the French name for the instrument - flute á bec.

At the other end of the recorder, another innovation was introduced by Peter Bressan - the addition of double holes for the lowest two notes. We take such luxuries for granted today, but this simple innovation makes the lowest semitones stronger and clearer - something that would become more important as music became more chromatic.

Many recorders have survived from the 18th century and can be seen in museums around the world. Fortunately contemporary makers have been allowed to examine these instruments and take measurements, resulting in modern copies for us to play today. Look at any recorder maker’s website and you’ll find recorders based on those by Peter Bressan, Jean-Jacques Rippert, Jacob Denner, Thomas Stanesby and others.

Inside the Baroque recorder

The Baroque recorder doesn’t just look different on the outside - the interior also changed to meet the demands of the new music. The headjoint remains almost cylindrical, but a taper is introduced through the body of the instrument, becoming most extreme at the footjoint. This taper has two purposes. From a practical point of view it allows for more comfortable placing of the fingerholes, but more importantly it greatly affects the sound of the instrument. Gone are the fruity low notes - the lowest tones are now much gentler. By way of compensation, the high notes are much stronger and easier to play - perfect for the florid passagework of Bach and his contemporaries. The Baroque recorder has a larger range too - at least two octaves and a note, but some composers (particularly Telemann) went further still, expecting players to reach the giddy heights of top C on the treble from time to time!

Mimicking the human voice

While recorders in C and F were the most common, a handful of other variations exist too. One of these is the Voice Flute - a recorder which sits between the treble and tenor, whose lowest note is D. The voice flute probably originated in the court of King Louis XIV of France, in Lully’s orchestra. It allowed recorder players to play music originally intended for the flute at the correct pitch. Of course its range, from the D above middle C also mimics that of the female human voice and this is likely to be the origin of its name.

It was commonplace during the Baroque to transpose flute music a minor third higher to place it within reach of the treble recorder. But this makes the music sound brighter and loses some of the mellower tonal qualities of the transverse flute. The voice flute, with its lower pitch, retains some of this character, while also being as agile as the treble recorder. Several original voice flutes survive today and modern copies based upon instruments by Bressan, Rippert and Stanesby are available for those who wish to explore this lovely sound world.

Other curiosities

Smaller recorders became less common during the Baroque period, but a handful of wonderful works exist for the higher instruments. Vivaldi composed three concertos for the ‘flautino’ or sopranino, although his scores also indicate that the music can be played a fourth lower on the descant.

The descant recorder and its close relatives also largely fell out of fashion at this time, although a handful of composers persisted with it in England. The names of such recorders often described their relationship to the treble recorder. Therefore the descant was a fifth flute because it’s pitched a fifth above the treble. It’s this recorder for which Giuseppe Sammartini, an Italian oboist working in London, composed his delightful concerto.

Alongside the descant there are two other variants. The fourth flute was pitched in B flat, a fourth above the treble and sounds rather mellower than the modern descant. It’s something of an anomaly, but two lovely suites by Dieupart survive for this instrument.

A more common small recorder (at least in England) was the sixth flute, sounding a sixth above the treble, and an octave above the voice flute. Three composers, William Babell, Robert Woodcock and John Baston, chose this as their instrument of choice for their charming concertos. These were almost certainly composed to be played between the acts of operas in London and the high pitch would no doubt have commanded the audience’s attention.

Should you invest in different types of recorder?

The decision of buy different types of recorders is a very personal one. If your playing comes as part of a massed ensemble, such as an SRP branch, a Baroque style recorder may suit your needs just fine.

On the other hand, if you play lots of Renaissance music, especially in smaller consorts, using historically appropriate instruments may help you get closer to the sound world of the period. Renaissance recorders require a different style of playing, from breath control to articulation, and can help you understand the music better. During my first year at music college our department invested in a double consort of Mollenhauer Kynseker recorders. We immediately noticed the difference. Suddenly we could use the appropriate articulation to bring out the cross rhythms and it was much easier to create sweetly tuned chords. Even when recording my consort videos now, I always use my Kynseker recorders for Renaissance repertoire and I hope perhaps you can hear some of these differences in the tone, style and articulation.

Ultimately your choice may come down to budget - after all, none of us have bottomless pockets. If this is the case and you have no plans to buy more recorders, I would still encourage you to at least try them when you have an opportunity - perhaps at an early music festival or during a recorder course where there’s an in house recorder shop. Trying a Renaissance recorder or voice flute for even a few minutes will give you a glimpse into these different sound worlds and a greater understanding of how the instruments we play can change the way we play the music written for them.